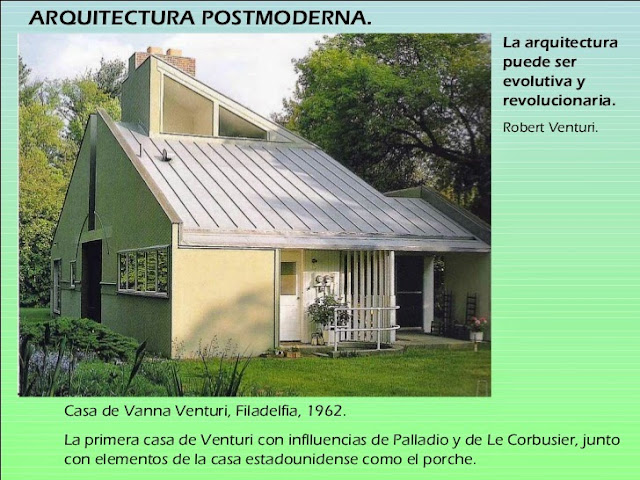

The Vanna Venturi House, one of the first prominent works of the postmodern architecture movement, is located in the neighborhood of Chestnut Hill in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was designed by architect Robert Venturi for his mother Vanna Venturi, and constructed between 1962 -1964. The house was sold in 1973 and remains a private residence.

The five-room house stands only about 9 m tall at the top of the chimney, but has a monumental front facade, an effect achieved by intentionally manipulating the architectural elements that indicate a building's scale. A non-structural applique arch and "hole in the wall" windows, among other elements, together with Venturi's book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture were an open challenge to Modernist orthodoxy. Architectural historian Vincent Scully called it "the biggest small building of the second half of the twentieth century.”

In 1959 Robert, Sr. died, leaving his wife enough money to build the house and live comfortably. The designs for the house by Robert, Jr. evolved over four years, but the architect noted only two indications of disagreement from his client. When the work was about three-fourths complete, she looked at the traditional 19th-century house next door and remarked "Oh, isn't that a nice house." She also rejected the marble floor in the dining area, considering it to be ostentatious, but relented as the house was nearing completion. Along with the Guild House, an apartment house for the elderly, also completed in 1964, the Vanna Venturi House was Venturi's first work as an independent architect.

Robert lived in the house until a few months after his 1967 marriage to Denise Scott Brown. Vanna Venturi lived in the house from 1964 though 1973. In 1973 she moved to a nursing home, and died in 1975. Venturi designed the Vanna Venturi House at the same time that he wrote his anti-Modernist polemic Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture in which he outlined his own architectural ideas.

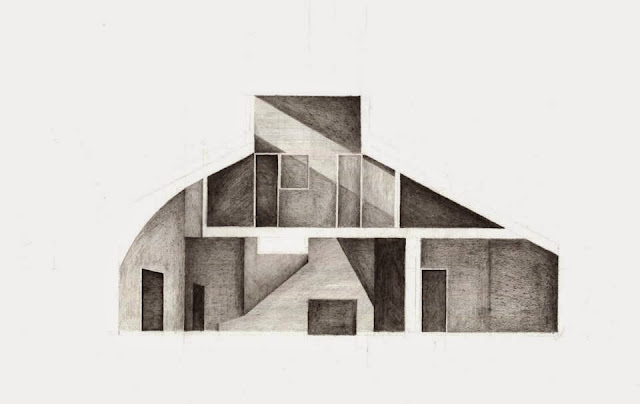

Many of the basic elements of the house are a reaction against standard Modernist architectural elements: the pitched roof rather than flat roof, the emphasis on the central hearth and chimney, a closed ground floor "set firmly on the ground" rather than the Modernist columns and glass walls which open up the ground floor. On the front elevation the broken pediment or gable and a purely ornamental applique arch reflect a return to Mannerist architecture and a rejection of Modernism.

Unusually, the gable is placed on the long side of the rectangle formed by the house, and there is no matching gable at the rear. The chimney is emphasized by the centrally placed room on the second floor, but the actual chimney is small and off-center. The effect is to magnify the scale of the small house and make the facade appear to be monumental. The scale magnifying effects are not carried over to the sides and rear of the house, thus making the house appear to be both large and small from different angles.

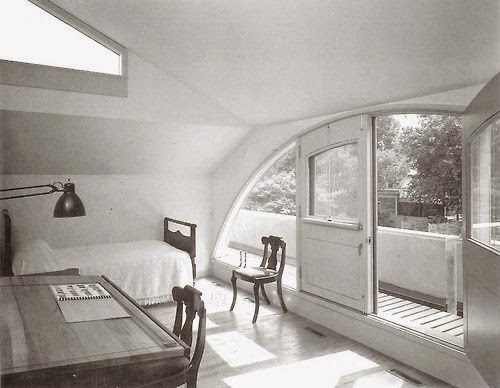

The central chimney and staircase dominate the interior of the house. This building recognizes complexities and contradictions: it is both complex and simple, open and closed, big and little; some of its elements are good on one level and bad on another its order accommodates the generic elements and of the house in general, and the circumstantial elements of a house in particular.